Climate change and Farmer’s adaptation in Nepal

Abstract

This study gives a clear picture of how Nepalese farmers are adapting to the climate change and how their adaptation strategies differ by geographical location. This report is based on the primacy data collected through the focus group discussion conducted with the farmers of hilly and terai district of Nepal. In addition this study suggests that adaptation strategies of Nepalese farmers are short term currently but such strategies need to be long term one if Nepalese agriculture sector is to cope properly with the climate change.

Keywords: Climate Change, Adaptation, Hill, Terai, Agriculture, Nepal

Introduction

Climate Change

Climate change is a globally accepted and experienced phenomenon. Various studies shows that its impact is more concentrated on developing and under developed countries where majority of poor people are dependent on subsistence agriculture. Nepal carries a very special case because with in very short distance, there is huge altitudinal diversity and simultaneous diverse climate change impacts can be found (Manandhar, Vogt, Perret, & Kazama, 2011).

Adaptation

In Nepal, NAPA and LAPA are some of the policy level initiatives undertaken by governmental and non-governmental agencies to enhance adaptation capacity of Nepalese farmers (Tiwari, Balla, & Pokharel, 2012). These scholarly attempts suggest that subsistence farmers are at the most vulnerable group to Climate change (IPCC, 2007).

Though Nepal’s share in Climate is negligibly small, the impact is relatively clear and high due to altitudinal diversity of Nepal’s topography. The population of Nepal is less than 0.4% of the world population and anthropogenic activity produce greenhouse gas emissions that account to just 0.025% of total greenhouse emissions.

Governmental reports rank Nepal as one of the most climate vulnerable countries in the world (GON, 2011) though The Nepal’s share in CC is negligibly small. The population of Nepal is less than 0.4% of the world population and is responsible for only about 0.025% of annual greenhouse gas emissions (NAPA\MOE, 2010).

.

Climate Change Impact

The impacts of Climate change are diverse and often debatable because they are coming from different sources and under different research framework. National Adaptation Programme of Action ( NAPA)- Nepal (2010) has points out six major areas of CC impact namely Agriculture and Food security, Water resources, Climate induced disaster, Forest and biodiversity, Public health and Urban settlement and infrastructure (Tiwari, Balla, & Pokharel, 2012).

The concerned stakeholders and institutions in CC sector are monitoring the Climate data and observing more intense, highly variable, longer gaps of no rain and delayed monsoon. In addition, growing number of glacier lakes and their growing size have high chance of cracking through terminal moraines and cause catastrophic floods. These CC consequences are anticipated to disturb irrigation and drinking water supply as well as hydroelectric production (WECS, 2011). In addition there are several anomalies predicted that includes biodiversity loss, desertification, glacier melting, and fresh water availability are often interlinked in complex system (Regmi et al., 2009). Global CC will also likely shift monsoon precipitation patterns in ways that will threaten particularly agricultural production in developing countries like Nepal (Tiwari, Balla, & Pokharel, 2012).

The vulnerability level can be also assessed from the food security perspective. Nearly 21 percent of the crop area is irrigated in Nepal (Panta, 2009). A slight change in the climatic variability has high chance of inducing of large changes in agricultural production. Scholars opine that Extreme weather conditions such as flood, drought, frost, hailstone and heat and cold waves are direct hazards to the agriculture production. For example Local consultation in Myagdi district revealed Ecoline shift in Myagdi district which might be due to increased temperature.

A recent example of shift of organize production region reflects the impact of CC in Nepal’s mountain region. In general, orange production takes place at 1200 to 1600 m. But at present it is observed that orange is found at the 1700 m altitude, Gauva also grow in high altitude (Tiwari, Balla, & Pokharel, 2012). Similar shift is observed in human habitation too. It is reported that inhabitants of Surkhang VDC in the Mustang district has migrated from that place due to drying up of water sources.

CC study in Nepal

CC study in Nepal is more focused on finding how Nepal is coping the CC impact. The researches analyses the mode and accuracy of farmers perception of climate change phenomena. Scientists carry out study to discover the new adaptation measures for farmers and people who are vulnerable to CC in Nepal’s mountainous area (Manandhar, Vogt, Perret, & Kazama, 2011).

CC study in Nepal acknowledges the role of different institutions in driving the CC discourse ahead. It confirms the climate change perception acutely and find how farmers respond to it appropriately. Nepalese farmers have their own indigenous knowledge and experiences to deal with the climatic changes around them while they are found adopting various agricultural and non-agricultural adaption measures at an individual level.

Climate Change and Geographical diversity

Farmer’s adaptation in Terai

There is changing trends among farmers behavior as a response to CC impact in agriculture sector in terai. Farmer in terai districts is found to shift from rice planting to fish farming. They prefer to farm crop that requires less water, mature early and has high tolerance to flood and other extreme climatic events. Terai farmers have started off farm activities like brick factories, driving rickshaws, porters etc, adopting zero tillage and surface seeding as strategies to adapt to particular CC impacts in their region.

On the basis of Focus group discussion and survey, the experience of the farmers of Sindhuli district would be relevant to understand the issue.

Two Case studies of Sindhuli districts

Untimely rainfall and decreased production in Jalkanya VDC

Poor farmers of Jalkanya VDC complain about increased temperature and decreased rainfall regarding the climate change. Farmer complains about the secondary impact of climate change for example they feel like there is increased deficiency of rainfall and subsequent drying of water sources in the village. Such unexpected phenomenon had resulted in soil hardening (difficult to break) and growing of shrubs more frequently in the paddy field. That increased the amount of labor to maintain the same level of production.

When asked about the climate information of the village in the 2 or 3 decade period, farmers especially depended on subsistent farming, which often had land on hill side with no possibility of irrigation canal to reach and soil of very bad quality, do feel that untimely and decreased rainfall had been the major problem in their agriculture. In one way it had decreased their production and stopped their regular farming cycle while in other hand such changes in climate like amount of rainfall and change in temperature had increased their cost of production. For example if the more amount of wild grass are seen in the paddy field, it need more labor to wipe them. If untimely rainfall occurs or rainfall doesn’t come as per the prediction of the farmer and their preparation of the rice plant, then their preparation cost goes to vain.

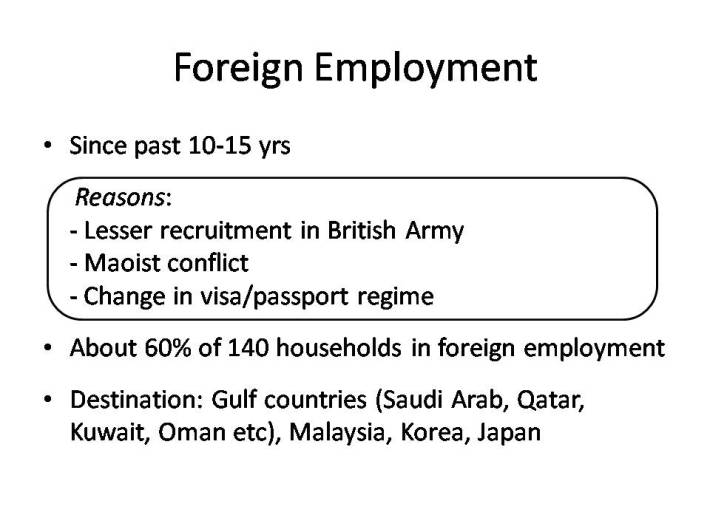

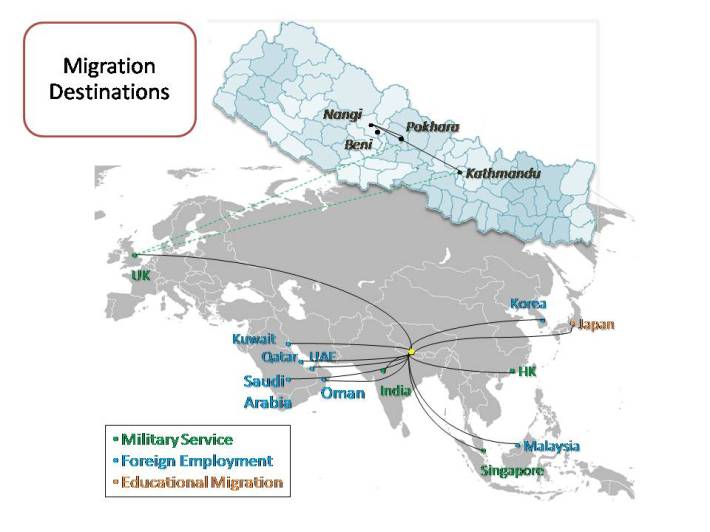

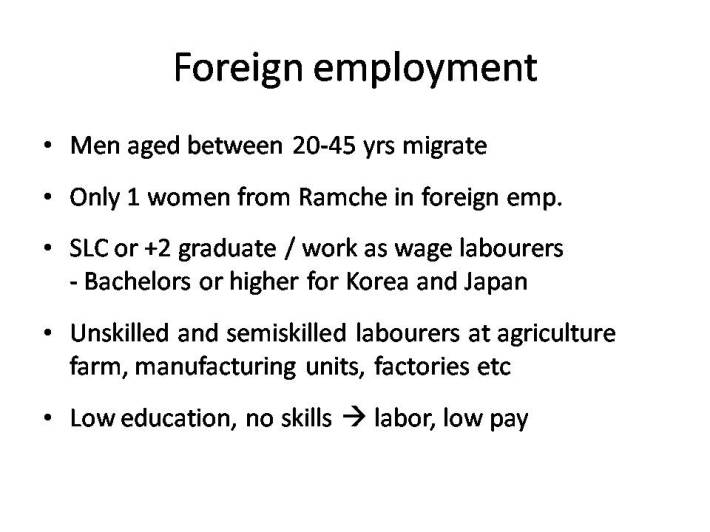

Regarding the farmer’s capacity to adapt to the climate change, most of the farmers were seen to be quite unknown about the need to adapt the farming mode. They were more worried about cursing the low rainfall and criticizing the VDC and government for not being able to manage irrigation for their land. Being unable to adapt to climate change and its negative impact on their production, farmer were moving towards foreign job employment opportunities for their younger generations in one side and on other side they were losing young labor to work on their field. Especially India and Malaysia were their target foreign country.

2 decades back, most of the farmers who are above 40 years now were young and they do feel that the summer temperature had apparently increased but their perception over winter temperature remained mixed and unclear. They shared that partly it may be due to their old age factor that in cold winter also they feel as colder as they used to 2 decade back. While this experience contradict with the local people of relatively young age who shared that winter are less cold than that of their grandfather’s time. Also, all villagers do agree with one another experience of dry summer than past.

Rainfall had become rare and shorter in the VDC. Some shared that rain fall comes at once and vanish in shorter period even before the soil gets completely moist or wet.

Farmers especially that of Tamang community (Janajati) responded that climate change had made their living harder. Decrease in the production of the maize and paddy, the poor farmers have no other options than to enter local forest and earn livelihood through fodder collection and firewood selling. Higher caste people in the village often interpret this situation of poor farmers especially dalit and Tamang that they don’t have energy to work on field, and jus waste their time by drinking alcohol and illegally degrade local community forest. A kind of conflict exists in local dialect according to local people.

Some farmers, relatively well off, shared very interesting experience regarding the impact of climate change. They do feel that increase in temperature of summer during last 2-3 decade has benefitted them like new appropriate environment for cauliflower vegetable farming. Also simultaneously new kind of diseases, which were not common some decades ago were seen to be attacking the vegetables and plants were found in the village.

The drought had become relatively longer and harmful in compare to earlier one. The stopping of wheat is one of the consequences of that drought during winter.

There were similar hardships faced by the farmers of Raanichuri VDC of Sindhuli Districts.

CC impact both positive and negative in Raanichuri VDC

The geographical location of this VDC is relatively remote and settlements are widely scattered among 8-10 hilltop such that no or very rare agricultural land seems to have reach of nearby water resources or stream for irrigation. Poor farmers shared that the rainfall has visibly decreased in 2 decades but oppositely the increase in temperature has made them feel comfort. Warm winters have relived the older farmers for whom working in winter during their young age was very difficult task.

Overall, the poor farmers have experienced both positive and negative impact of climate change however it is often negative most of time.

Farmer’s adaptation in Mountain

The trend of farmer’s adaption in mountain is different form terai. Farmers are more attracted to new kind of tourism business while previously they were surviving by traditional agricultural practices. They have adopted diversification of crops that includes farming of cucumber, bean, tomato, pumpkin and chili. These diverse crop are farmed both in open and green house. Local development partners have followed kitchen waste water harvesting technologies to fight water shortage. Recently farmers of apple farms have stared promoting apple farming to new election and region. Despite all this new trend of farmers adaption, mountain people still followed non-agricultural adaptation measure to conduct their agricultural and other activities like consulting traditional Lamas.

Climate change experience of hilly districts like Kavre of Nepal would be relevant to understand the aforementioned impact.

Two case studies of Kavre districts

More impact on Farmer’s livelihood in Kusadevi VDC

Kusadevi VDC is spread over 40 settlements while the climate change information has been collected from 6 settlements spread over different wards of the VDC. The VDV exist in average 65000 feet from the sea level. The area has ‘samasitosna pradesiya’ climate. The average temperate is 15-30 degree Celsius. The area is dry in the winter while in summer, it receives average rainfall. The agricultural practices differ according to the availability of the irrigational facilities and the technical knowledge of the farmers.

According to farmers of Kusadevi village, climate change has been experienced through increased temperature and subsequent opening of vegetables especially cauliflower and other cash crop, which was not possible some decades ago due to relatively lower temperature.

Climate change has also led to drying of water resources and its bad impact on poor farmers’ livelihood who are heavily dependent on farming.

Increased use of fertilizer has become necessary to main production- this had also been understood by farmers as the impact of climate change.

According to farmer, it’s difficult to predict rainfall and the drought are relative longer and than that of 2-3 decade back. But interestingly, farmers in Kusadevi VDC were found adapting to climate change through different technique like orange farming, extensive farming, off season vegetable farming and rotational farming and greenhouse mode of farming.

Farmers are happy regarding increase in temperature of the location in compare to 2 decade back as they have irrigation facilities to conduct acceptable and cash crop farming.

Similar experiences were shared by the farmers of Dhungkharka VDC of Kavre district of Nepal.

Farmers enjoying the benefit of CC in Dhungkharka VDC

Dhungkharka lies at 23 km south of Dhulikhel, the headquarter of Kavre district of Nepal. There are 23 settlements in the area spread over mainly two type of land structure including high land and low land. The VDC extends from 1300 m to 3018 m from the sea level having different kind of agricultural production. In the low land, rice, maize, wheat and vegetable farming is common while maize farming is the main agricultural activity along with milk selling and livestock raising. As 2001 VDC profile of the VDC, majority of residents are engaged in agriculture, 30% in studies and unemployed activities, 5% in daily wage labor, 0.5% in industry and 2% in business. Only 74% male and 62% female are literature. Among the entire household, 155 household were categories under extreme poverty which include Dalit and Tamang populations.

There were diverse experiences of farmers especially poor farmers regarding the impact of climate change in their agricultural practices. Some farmers feel that shorter and heavy rainfall which used to be seen some 20 years ago was missing in the present time. They complain about frequent occurrence of drought for longer time in compare to past.

Most of the farmers were dependent on sky rainfall and low rainfall or drought had been main obstacle in continuing their farming. They think that if they had irrigation facilities, they would have combat with any climate change problem like decreased rainfall or increased temperature.

Among some farmers, zero production of Rice is the main reason behind low or untimely rainfall and absence of irrigation facilities.

Subsistence farmers shared that snow fall was common before 1 or more decades back and that was acting as the natural killer of the disease but the absence of snow fall since some decades is allowing the same disease in potato to grow and destroy the crop.

Climate change is not followed by only negative consequences among poor farmers of Dhungkharka. Positive impact of climate change includes appropriate environment for cash crop especially vegetable (cabbage) which had no possibility of growing 15-20 years back. Similarly less cold environment during winter has created appropriate environment for the growing of new kind vegetable and cash crops. Simultaneously

In Dhungkharka there is increased use of fertilizer for maize cultivation. That was in response to the decreased productivity of maize due to low soil quality.

Most of the farmers shared that they were not adapting to the climate in their farming mode. However among few farmers who were able to adapt to the climate change, were following interesting technique to increase their agricultural productivity. One of them were ‘Dyang’ in local language that refers to the making soil mass in farm or agriculture land. That is expected to decrease the amount of seed to be shown with same amount of productivity.

Farmers’ adaptation in Terai Vs Mountain

Two case studies have been carried out to mark the trend in climate change scenarios and farmer’s adaption pattern between lowland Terai and upper land mountain of Nepal (Manandhar, Vogt, Perret, & Kazama, 2011).

Farmer’s adaption in Nepal is characterized by their variation in their responses in two different geographical regions namely Lowland terai and upper land mountain.

Terai observes relatively less climatic variation in compare to upper land mountain because altitude different is sharp and high in mountain region. Generally terai farmers are found to be suffering of the CC impact like flood and drought while that of Mountain have benefitted from CC in one way or the other. There are different factors that are acting either facilitator or barrier to combat CC impacts in Nepal.

The dissemination and adoption of new technologies, agricultural inputs, information and innovations are observed faster and easier in terai region in compare to upper land mountain which is dominantly covered with rugged mountains. In Mustang district of Nepal, an example of upper land mountain region of Nepal, Lamas, the traditional fortune teller do weather forecasting and suggest appropriate time schedule for local farmers to start plantation. That hints, enough information and technologies to have access to CC information is not available in Mountain region.

The planners and farmers stress on different mechanism to fight with CC change in Nepal. There is of strong irrigation channel and drainage systems in terai while crop diversification is highly practices in upper mountain region.

Conclusion

The literature review and the focus group discussion with local farmers suggest that the adaptation capacity seems fragile and short term and hence scholars recommend for long term coping mechanisms. Similarly the local and indigenous method of coping with CC change practiced for generations in mountain area can’t be underestimated. In addition, rather than generalizing the coping mechanisms of other places, Nepal should develop location specific adaptation strategies and encourage sustainable farm management practices and dissemination low cost technologies.

References

Grothmann, T., & Patt, A. (2005). Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change , 15 (3), 199-213.

Gum, W., Singh, P. M., & Emmett, B. (2009). CLIMATE CHANGE, POVERTY AND ADAPTATION IN NEPAL. (W. Gum, Ed.) Lalitpur, Nepal: Oxfam International.

Howden, M. S. (2007). Adapting agriculture to climate change. National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America .

Manandhar, S., Kazama, F., Dietrich, S., & Sylvain, P. (2011). Adapting Cropping systems to Climate Change in Nepal: a cross-regional study of farmer’s perception and practices. Regional Environmental change , 348.

Manandhar, S., Vogt, D. S., Perret, S. R., & Kazama, F. (2011). Adapting cropping systems to climate change in Nepal: a cross-regional study of farmers perception and practices. Reg Environ Change , 335-348.

Tiwari, K., Balla, M., & Pokharel, R. R. (2012). Climate Change Impact, Adaptation Practices and Policy in Nepal Himalaya. UNU-WIDER. Helsinki: United Nations University.

SWT – School to Work Transition

Executive Summary

Primarily, this text is an attempt to explore what aspects of the school to work transition discussed in the academia. Secondly, the role of public employment agency in the school to work transition process will be explored. If, possible further research area will be sought. (The researcher can be contacted at kushekharkc@gmail.com)

Key words

“transition”, “school to work”, “world of work”, “labour market”, “job placement”, “efficiency”, “employability”, “public employment agency”, “job brokerage” and “job centre”, “job centre Plus”, “work agency”, “Public Employment Service”, “Employment Service Center”

1. Concept/definition

School to work transition, at elemental level of understanding, is the period during which an individual leaves school and starts employment (Ng & Feldman, 2007, p. 115) but as per Ryan (2001, p. 34), various issues are included in the study of the school to work transition that concern schooling, employment, and training. It includes the operational and outcome aspect of the existing (and former) educational and training systems and various necessary attributes like occupational knowledge, skills and attitudes along with all other efforts that enable one to adapt and adjust to the social and environmental demands of a job whether it is formal or informal or mixed contexts characterized by the “diffusion” of learning and earning (Pastore, 2018, p. 6; Riesen, Schultz, Morgan, & Kupferman, 2014; Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017).

As Quintini, Martin, and Martin (2007) state

“The transition from school to work is difficult for young adults and can take on various forms – an immediate and brutal path from school to work, vocational training or casual job or part-time work undertaken at the same time as school” (p.6)

Below themes represents some of frequently mentioned or recurring themes in the literatures of SWT (around 30 studies) that drives the academic discussion of SWT at different level of concepts, activities, program, institutions and policies. Be it rich or poor economies, formal or informal learning/earning space, altogether these themes will provide an introductory framework to understand the totality of the school to work transition trajectories and dynamics.

2. Effective partnership for lifelong learning

It’s interesting to notice that, despite vast array of program and policies on school to work transition process, whether be it active, passive or mixed one (like flexicurity[1]), all directly or indirectly implying the lifelong learning as the outcome of all effort and initiatives at national and local level across the countries through effective partnership(Lindsay, McQuaid, & Dutton, 2008; Ravenhall, 2018). They appear in the form of either national level policy and programs initiatives or local partnerships models mostly in European, US and Canadian context and few in Asian and African contexts, mainly to fight with unemployment. Mostly explored aspect of these programs are various contexts and factors that impacted on the efficiency, effectiveness, relevance and success aspect of the school to work transition process.

Agreeing to the notion of any agency ‘can’t do it alone’(Lindsay et al., 2008, p. 727), there is a growing voice over the necessity of one or the other ways of effective partnership among stakeholders in transition process or labour market to ensure the desirable outcome of efforts and initiatives for efficient and effective school to work transition process. The objective of education and learning is looked beyond the ‘narrowed’ employability objectives of fulfilling the need of the labour market and extends to the capability of self-fullment and full participation in social, civic and community life(Ravenhall, 2018, p. 9).

Many employability initiatives in UK like ‘Pathways to Work’ and ‘Working Neighbourhoods’ during the start of the 21st century provides basis for the significance of the effective partnerships among public employment services, private employability services, community organizations and related government agency. Overcoming the challenges resulting from organizational culture of ‘contractualism’ and ‘centralised localism’ in employability initiatives of UK government, Lindsay et al. (2008) suggest for an innovative partnership model of ‘inter-agency cooperation’ which is believed to deliver various benefits; address the multidimensional challenges faced by vulnerable and disadvantage groups; explore innovative approaches to intervention, maximize the impact in terms of quality and diversity of services, ensure the availability of necessary resources, capacity building of community and voluntary organization, enhancement of local knowledge, stakeholder networking and social capital enhancement(Lindsay et al., 2008, pp. 719-728).

No coherence is found in the pattern of outcomes of the various integration programs. Reports confirm that the implementation of the diverse labour market structural reforms (for e.g. unemployment benefits, labour market flexibilization, wage setting policies, employment protection legislation) doesn’t necessarily bring desired labour market outcomes like decreasing unemployment and income gap. The case of European labour market policies[2] and their impact through reform initiatives like Job Acts, European Youth Guarantee (EYG) shows mixed results and there is no universal agreement over the relationship between the interventions and their outcomes. The literature hints at the consideration of various technological and globalization factors on the effectiveness and efficiency of the labour market reform initiatives (Avis, 2016; Dosi, Pereira, Roventini, & Virgillito, 2016; Pastore, 2018).

Cross-country interventions and results are note-worthy for discussion owing to experience of intervention of similar programs but diverse results; Finland shows success rate of job placement and short term training program while the Swedish equivalent program failed (Quintini et al., 2007, p. 16). To tackle the growing problem of long-term unemployment and availability of job offers for new entrants in European labour market[3], European Youth Guarantee (EYG) came into being in 2015, mostly focused on protecting employment. To address the multiple aspects of SWT, more holistic approaches like WBL (Work Place Learning)[4], also came into place which in addition to employment protection approach, also ensured support and services from school level to adulthood in terms of growing employability skills and knowledge in work place settings (Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017, p. 15).

Somewhat similar to European model of WBL and EYG but focusing more on opening up the introductory aspect of the world of work to school students and learners, work integrated learning (WIL) emphasizes on the ‘goodness’ of work placement practices and all other schemes like internships, field work, sandwich year degrees, job shadowing and cooperative education as an integral part of the quality school to work transition.

Lifelong learning is emphasized as one common outcome of an active labour market program like VET, considering the needs of the people from formal and informal learning contexts not excluding in-school and out-of-school youth. UNESCO establishes the ‘lifelong learning’ as the guiding principle for right to education for all and encourage all age group’s access to learning opportunities beyond formal settings like schools, university and informal settings like community learning centres (Ravenhall, 2018, p. 11). Experiences of the training in low income countries indicates the popularity of the technical and vocational skill development (TVSD) in compare to traditionally used TVET (technical and vocational education and training) or VET, which basically include 3 components namely 1) formal public school based training and education, 2) vocational training linked with industrial work place and 3) apprenticeships in non-formal setting like craftsmen (Hartl, 2009, p. 5). However, rich economies may have different scenario.

Apprenticeships varies in its functional and structural forms across the European union member states, overall regarded efficient in supporting school-to-work transition of young people in enhancing their employability. As per the cross-country studies of 30 countries in Europe, it was observed that basically 3 categories of apprenticeship existed based on function and purposes they were serving in the countries. All the categories include some or all features of work-based learning (where employers engagement was prioritised) or formal VET delivery system (where polytechnic colleges were burdened with practical learning) or mixture of both. Literature admits that efforts were made to incorporate new features of aprenticeship, adding challenges to create a standard and effective form of apprenticenship in Europe (Training, 2018, p. 74).

Various innovative methods were explored. ‘Training Credit’[5], was implemented in Britain in 1970s, based on strategic objective of serving dual objectives; serve the interest and convenience of students needs as well as foster quality of training outcomes (Hodkinson, Hodkinson, & Sparkes, 2013, p. 17). Some posit the idea of ‘Training Career adaptability’ as an effective training model for graduates who are vulnerable to under employment in the bad economic situation of the country and suffering from difficult transitions. This training tool comprises four competencies namely concern (looking ahead to one’s future, control (identifying career of one’s interest), curiosity (looking around at career options) and confidence (genuine desire for actions leading to career goals) and enables the graduates’ to undertake high quality jobs(Koen, Klehe, & Van Vianen, 2012, pp. 396-407).

The ‘New Deal partnerships’ program implemented in UK can be seen as an active labour market program implemented in UK during 2006 with the successful record of harnessing local partnership, legitimizing the employability initiatives of UK government and delivering quality services to the residents of hard-reach areas. Declaration of ‘Employment Zones’ were strategically important in terms how they were targeted at relatively ‘economically inactive’ areas and how local community knowledge and social capital were valuable in legitimizing the employability policy initiatives. Neither the role of private employability agencies like ‘the lead partnerships’ nor the ‘local employment partnership’ based local partnership was undermined. This model is still claimed to be one of the successful model in decreasing unemployment in UK (Lindsay et al., 2008, p. 721).

Apart from the aforementioned programs, various career development programs are available usually in a formal settings like schools, somewhat similar, sometime overlapping with each other and at other time mutually exclusive: for e.g. career interest assessments, career aptitude assessments, carer or job counselling, career exploration courses, tech-prep program, writing career plans for students, mentorship programs with employers, job fairs, interviewing or resume-writing practices, career or job resource center, tours of colleges and technical schools as well as industries and business houses, speakers from local business, college fairs or college days etc focus on efforts to orient students towards the introductory aspects of the world of work, mostly theoretical and based on discussion, sharing and observation. While other programs like apprenticeship, cooperation education program, school-based enterprises or business and job placement actively expects the student to learn practical aspect of the world of work and gain employability skills through practice and experiences. (Carter, Trainor, Cakiroglu, Swedeen, & Owens, 2010; Jackson, 2015, p. 17). All or some of these programs are considered in various modality of programs implemented across the countries, especially in European Union member states.

In Britain, the classroom based ‘cubical box’ learning system is considered no more effective ways to prepare youth people of 21st generation for the world of work considering the job market characterised by uncertainty, connectivity, employment volatility and surprising demand of new and competitive skills, knowledge and experiences as well as capability to tackle unfamiliar and ‘alien’ challenges. Criticising traditional schools as ‘neighbourhood learning centres’, researcher suggests for a broader and deeper but open and active lifelong learning system based on partnership among schools (with brokerage or service providing role), employers, voluntary and religious organizations, parents and young people, which will prepare young generation not only to tackle challenges of adult life but, in real sense, to develop learning relationships, problem solving and transferable skills[6] and become capable of solving/addressing new, unfamiliar and complex problems in workplace, family and society. Only this ways the society is expected to made a ‘quantum leap’ in education performance (Bentley, 2012, pp. 15-18).

While the debate between the need as well as relevance of active and passive labour market policies have been continuing, theoretical discussions have started on the middle way between active labour market and unemployment insurance in Europe by putting light on the significance of strong employment insurance system; that will enhance risk sharing abilities of individual not only during their ‘full-time or permanent job’ period but also throughout their life course transition in Europe (Schmid, 2015, p. 72). Similarly, In United States, policy efforts are made to integrate all best features of school to work transition into a single concept ‘Seamless Transition characterized by classroom environment supplemented by employment preparation, general education inclusion, parent involvement, social skills training and self-determination training, to materialize the concept of successful transition from school to the world of work (Wehman, 2013) .

Overall, a more open, active and community-based lifelong learning system and inclusive labour market programs ‘not limited within classroom’ are believed to contribute to a successful school to work transition processes, that not only focus on initiatives aimed at growing human capabilities like education, experience, knowledge, skills, aspirations and confidence but also sustaining the employability and addressing the risks throughout the life courses (Bentley, 2012, p. 2; Wehman, 2013, p. 60).

3. Concern for Disadvantaged Groups

Whether it be in the form of ‘learning society’ model of education where the young generation are expected to learn lifelong skills and meaningful relationships between them and society or the burgeoning agenda of ‘Labour Market Inclusion’ where everyone of working age are expected and encouraged to participate in paid work, one of the seriously targeted principle of labour market integration program is the protection and inclusion of vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society (Bentley, 2012, p. 18; Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017, p. 4).

An critical aspect of school to work transition is questioned by Willis (2017) [7]; how and why disadvantageous youth are restricted to high paying job opportunities and limited to manual and “working class culture” jobs in labour-intensive industries; how the historical characteristics of the places they live and state-imposed cultural and political conditions lead their decision to develop natural acceptance “self-damnation’ towards choices available in the particular ‘historical and cultural’ settings (Carter, Ditchman, et al., 2010, p. 22; Carter, Trainor, et al., 2010; Riesen et al., 2014).

While the SWT issues in rich economies like that of European Union member states and US is dominated by policy focuses on competitiveness, technological innovation and entrepreneurial supports, it’s interesting to note that the government of low-income and conflict affected countries are struggling to sustain basic education outcomes like primary enrolment rate and school complete rate and equitable access to low and middle skills development program. Poor countries largely lack socially, financially and technically, the capacity to link education and training outcomes with labour absorption capacity of the job market (Avis, 2016).

A review on India’s SWT status admits that the ‘low class’ social and cultural perception towards the VET stream[8] of learning in compare to the general academic stream, has resulted in the oversupply of ‘worker without specific skills’ and resulting in the pervasive skill mismatch and a ‘only’ hard situation for ‘hopeless’ youth; to fly to gulf countries mostly for labour intensive work opportunities. There are increasing voice for shifting education policy from general to VET and don’t leave anyone behind especially those from informal learning settings and rural areas including vulnerable group like women and ex-combatants so as to enable them to take better jobs or open up career pathways (Avis, 2016; Hartl, 2009). Even rich economies like US also faces chronic underemployment and unemployment despite various legislation and policies adoption on empowering people with disability (Riesen et al., 2014; Wehman, 2013, p. 58).

Pastore (2018) acknowledges the reality that the capacity of the state, society and family in managing shock and burden of unemployment is not same all over the world. Depending upon the availability of necessary supports and resources for overcoming difficulties in the transition, strategic approaches are needed, without overlooking on the global challenges like financial shocks, global unemployment, technological interdependence, changing education system, growing mismatch between skills and profession etc. Some refer to the social contexts of inequality and power relations, resulting in disproportionate benefit and burden of job opportunity and unemployment respectively. Inclusive labour market appears as the major enabling characteristic of the labour market in the literatures, often presented as the growing concerns among foreign aid donors and developing countries to address the skill and employment gap of unemployed especially socially disadvantaged long term unemployed refugees, immigrants and so on, so as to enable their smooth transition toward the world of work, owing to their historical exclusion from the standard school-to-work transition schemes (Pastore, 2018, p. 8; Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017, p. 9).

Ensuring equitable access to available job opportunities with the reinforcement of all necessary transition supports for job seekers, both school graduates and school leavers, and reform of education policies through shift from general education or vocational and technical education seems to dominate the policy focus of most of the OECD countries. Similar experiences are shared by rich economies, especially EU and have established history of implemented programs focused on addressing education, training and employment needs of disadvantage groups, which also include social assistance, housing support, childcare and health services.

Rurality as one of the disadvantageous aspects of development when accompanied by one or more of the challenges like poverty, low education, gender inequality, illiteracy, limited transportation, hard geography and insufficient provision of training canters, all acts as a distinct set of barriers to the inclusive development of the youth and disadvantage group in particular (Hartl, 2009, pp. 2-8).

Including disadvantaged groups into all phases of SWT remains a burgeoning challenge to the contemporary world as there are global concerns, especially from international development agencies like EU and United Nations, for district barriers faced by ethnic and gender minorities, third world nationalities, low profile university graduates, newly arriving immigrants especially from refugee and asylum background, low-skilled people, senior citizens, people with physical and emotional impairment or disability. Most of the initiatives with concerns for disadvantaged groups are aimed at enabling unemployed with skills, experience and confidence to tackle the personal, educational, family, social and professional barriers to education, training, work exposure and sustainable job placement services available in the country (Grant-Smith & McDonald, 2018, p. 3; Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017).

As discussed above, the number and the intensity of the challenges increases in the case of people with disability. Literatures vividly stresses on the long list of lacking factors for facilitating the transition of people with disability from school to a decent job, among which the knowledge of transition process and availability of community resources, necessary employability skills, knowledge and confidence and family’s support and interest in the career progression of their child with disability are lacking strikingly.

Quoting a successful story of young boy with autism, a focus on best practices like community participation, availability of internship opportunities, positive behaviours help, better coordination among responsible agency, technological skills and family’s support are made to enable someone with disability live a happy, independent and active life (Wehman, 2013, p. 58). Despite the experiences of different type of intervention, there is little disagreement about the contributory role of collaborative effort of schools, community, families, agencies, employers and state in enabling a successful school to work transition of youth, especially coming from disability background (Coetzee & Beukes, 2010, p. 195; Grant-Smith & McDonald, 2018, p. 16)

Drawing the development experiences from low income countries in Asia and Africa, many admit that the capacity building efforts aimed at enhancing the employability of disadvantaged youth especially women can be achieved by increased strategic investment in provision of quality training centres with technically and socially sound teachers/trainer, hostels and cafeteria and other logistic support. Equally important factors are the implementation of people-centred pedagogy linked with local production practices and sufficient number of certified women trainers leading to a gender balanced perspective towards training and education. Many interventions are targeted at integrating and upskilling vulnerable groups such as young ex-combatant, orphans, and people with disability into proper process of school to work transition (Hartl, 2009, p. 20).

Another perspective to address the concerns for disadvantaged group may be exploring the factors that are preventing young adults often referred as NEET (not in education, employment or training) from all aspects of transition to opportunities for education, training and employment (Canada, 2018).

4. Public Employment Agencies/Services

Public Employment Agency (PEA) is a government entity, usually responsible for assisting citizens for job search, vocational guidance and distribution of unemployment benefits (Fougere, Pradel, & Roger, 2009). Nevertheless, its functions may be one or more of the above functional items across the countries depending upon the nature of the labour market and development status of the countries (Thuy, Hansen, Price, & Perret-Nguyên, 2001). There are private employment agencies too, which do similar functions often more ‘intense and costly services’ but target different type of job seekers, usually who can afford job search cost (Fay, 1997; Rehwald, Rosholm, & Svarer, 2017).

Different terms represent the public employment agencies across the world; ‘job brokerage agencies’ in Europe (Launov & Wälde, 2016), Public Employment Service in various member states of ILO(Thuy et al., 2001), employment service office in Australia (Fay, 1997), public employment service in Sweden (Höglund, Holmgren Caicedo, & Mårtensson, 2018), job centre in South Korea[9] and Jobcentre plus in UK (Lindsay et al., 2008, p. 722), Employment Service Centre (ESC) in Nepal[10] , temporary work agency and so on.

Personnel working in the PEAs, depending upon their role and level are also recognized by different names including job broker in Europe (Commission, 2016), employment counsellor in Nepal[11], job agents, placement officers, employment out-reach personnel and employment specialist in Taiwan, employment advisor in France (Sultana & Watts, 2006), employment coaches in UK (Lindsay et al., 2008, p. 726)and case managers in Australia (Fay, 1997) and so on.

Public Employment Service (PES) have history of existence since around the end of the 19th century mainly to tackle the socio-economic challenges posed by the unemployment however it was ILO (established in 1919) which formally established PES in different developing countries. During World War II, PESs were involved in job broking or labour exchange and distribution of unemployment benefit however after 1970s, owning to high growth of unemployment, PES became government entity in developing countries for developing employment policies and labour market programs. Around 1990s, owing to the growing impact of economic liberalisation and globalization, there were emergence of private employment agencies (Thuy et al., 2001).

What role does PESs play in SWT?

PESs are administrative and government bodies responsible for successful implementation of labour market reform programs implemented by the state, targeted usually for job seekers from disadvantaged groups. For e.g. Germany actively seek support from employment service agency in integration of newly arrived refuges (Sachrajda & Burnell, 2017; Schmid, 2015). And UK had a successful story of implementing PES as an key implementing body to tackle the unemployment problem, especially hard reach areas and ‘economically inactive’ places (Hartl, 2009, p. 772; Lindsay et al., 2008).

PESs perform best and deliver efficient results when there are sufficient availability of human resources and financial funding to operate. PES should be free of bureaucratic hassles (often acting as barrier to accessing the employment services by people) for the delivery of quality services and assistance for people to exit from employment (Pastore, 2018).

PES can also be the official source of monitoring the school to work transition outcomes like unemployment, especially conducting research surveys and analysis of data-base produced by PES. The impactful linkages of employment agencies with unemployment is revealed in a quantitative study (standard search and matching model) which found out that the low matching efficiency of transition from unemployed to employment positions in Germany explains why Germany has high unemployment volatility than US and differences in other aspects of worker flows (inflow from employment to unemployment and outflow from unemployment to employment) (Jung & Kuhn, 2014; Thuy et al., 2001).

5. Minor Issues

- Digital Natives: More advanced and internet-based approach to capacitate learners and workers are suggested with the objective of enhancing productivity and firms’ competitiveness in informal learning places like firms. In line with this, the effect of Web 2[12] and social media on worker productivity and firm’s success are becoming an area of academic inquiry(Mamaqi, 2015). The significance of this approach become relevant in the current context of internet driven industries, where our so called ‘millennials’ or ‘digital natives’ don’t only have better multitasking, self-adaptation, cultural assets and thinking diversity, information filtering, networking and technology adaptation capabilities in compare to old generation but also embody respect, loyalty and agency to drive the organizational and social relations built by Gen X (Bentley, 2012, p. 11; Hershatter & Epstein, 2010).

- Social/Family Influence: Pastore (2018) admits the profound impact of various social factors like family influences, social class and perceived notion of education and training on the career choices and transition outcomes of the individuals.

In West Africa, rural youth are enrolled in non-formal apprenticeship not because of their self-motivation and awareness about choosing particular trade or occupation that matched their interest, but influenced by their father and grandfathers who have final say in the career transitions or even choose what forms training (carpentry, masonry, auto-mechanics welding, tailoring, dressmaking, cosmetics, hairdressing etc) these youth should participate. Parents see their children enrolment in apprenticeship program as a remedy to drop out pain during their teen, platform for socialisation and strategy to avoid being vulnerable low skilled labour migrants (Hartl, 2009, p. 5; Thorsen, 2011, p. 74).

Various social factors including family and peer learnings come into consideration to understand how success the school to work transition process will go. For e.g. how well any family will orient their children towards the world of work from their early childhood, school graduation and job searching phase to the need of life long career transition will have impact on how confident, professionally strong, alert, skilled and professionally satisfied he/she will demonstrate in the world of work (Ng & Feldman, 2007). The professional identity, one will grow from family upbringing, socialization, peers influence and all direct/assisted integration programs available in schools (either full/part time work or internship/apprenticeship) will sketch the transition trajectory from school life to adulthood and continue throughout the lifelong learning process (Quintini et al., 2007).

- Theory and Research Methods: Multiple theories and research methods were observed in the study of the various aspect of SWT. Role identity theory could be a framework to study how an individual’s self-identification process determine the active or passive growth in career pathways from school to the world of work while social capital theory could be of a guiding framework to study the accumulation of education and training capabilities in an individual and finally leading to desired transition outcomes and self-efficacy(Ng & Feldman, 2007).

Various studies adopts quantitative methods like IPA technique, partial equilibrium unemployment, standard search and matching model, reduced form model of job search, and structural model of job search etc in understanding and linking the role of public service centres and its effectiveness in delivering services like job search, job placement, and overall impact on the unemployment(Fougere et al., 2009; Rehwald et al., 2017; Van Ours, 1994).

- Duration of Transition: Unnecessarily Prolonged transition is looked upon as a challenge to smooth transition outcomes. Either long duration of studies or unwanted extension of unpaid internship or pursuing of vocational training without perceived confidence on returns, there are various forces like education level and employability into play in determining actual scenario of transition duration. For e.g. School leavers in European countries many take 2 or more years to find their first job and job seekers with low education attainment may get stuck in temporary job for long period of time, disabling them to find further career pathways (Pastore, 2018; Quintini et al., 2007, p. 20).

While some look gap in transition as challenges, in UK participating in gap year is considered as an opportunity. Sometime, taking break after leaving schools and before landing in the world of job is looked as an advantage to grow cultural capital, knowledge, and a life-changing experience of the nature and diverse people around the world. The practice of gap year[13] (break during job or studies), popular among rich economies like European countries and China, though seems to prolong a small aspect of the SWT, is actually claimed to have enhanced the employability of the individuals, making the participants distinctly, qualified, confident, skilled and more probable of being accepted by employer (Guomei & Wei, 2017). However, due consideration is to be made that in poor economies, most of the people have multiple restriction including strict visa filtering process[14] for travel access to various developed countries.

- Demography: Responding properly to the Demographic transition (decreasing fertility and mortality rate, growing ageing population, shrinking of active population age group of 15-59) has become a big headache for policy makers in China as they are struggling to sustain the economic growth in one hand and find balanced ways to afford the huge ageing population and supplement shrinking labour force with investment on technological innovation and productivity (Du & Yang, 2014, p. 630).

Conclusion

Following inferences can be derived from the academic discussions on the various aspects of the school to work transition.

- There is some level of agreement among researcher on the positive role of lifelong learning and effective partnerships (collaboration, inter-agency, multiagency) in the smooth passage of student/job seekers from school to adulthood, either by enabling the functioning of public employment services or maximizing the benefits of the education and training efforts.

- There is a coherence in agreement among researchers to find effective and innovative ways to include beneficiaries from disadvantaged groups often characterised by one or more of the rurality, disability, poverty, gender inequality, income disparity, exclusion from school and NEET (not in education, employment and training) etc.

- Researchers suggest that Public Employment Service Center play enabling role in effectively implementing the state policies and program focused on employability of the job seekers, not undermining the role of effective partnerships among employers, job seekers, VET providers, community agencies, families and all other partners who have role in the school to work transition process.

- Various socio-economic factors like education level, economic status of the country, health care services, demographic structures, political transitions of the country and family and social influences on individual’s choices may have backward and forward linkages to the school to work transition process.

References

Avis, J. (2016). India: preparation for the world of work: education system and school to work transition. In: Taylor & Francis.

Bentley, T. (2012). Learning beyond the classroom: Education for a changing world: Routledge.

Canada, S. (2018). The transition from school to work: the NEET (not in employment, education or training) indicator for 15 to 19 year olds in Canada. In. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Carter, E. W., Ditchman, N., Sun, Y., Trainor, A. A., Swedeen, B., & Owens, L. (2010). Summer employment and community experiences of transition-age youth with severe disabilities. Exceptional Children, 76(2), 194-212.

Carter, E. W., Trainor, A. A., Cakiroglu, O., Swedeen, B., & Owens, L. A. (2010). Availability of and access to career development activities for transition-age youth with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 33(1), 13-24.

Coetzee, M., & Beukes, C. J. (2010). Employability, emotional intelligence and career preparation support satisfaction among adolescents in the school-to-work transition phase. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 20(3), 439-446.

Commission, E. (2016). job broker project – competency and learning development for job brokers in the EU Intellectual Output 02

In (pp. 40). Europe: Job Broker.

Dosi, G., Pereira, M. C., Roventini, A., & Virgillito, M. E. (2016). The effects of labour market reforms upon unemployment and income inequalities: an agent-based model. Socio-Economic Review.

Du, Y., & Yang, C. (2014). Demographic transition and labour market changes: implications for economic development in China. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(4), 617-635.

Fay, R. G. (1997). Making the public employment service more effective through the introduction of market signals.

Fougere, D., Pradel, J., & Roger, M. (2009). Does the public employment service affect search effort and outcomes? European Economic Review, 53(7), 846-869.

Grant-Smith, D., & McDonald, P. (2018). Planning to work for free: Building the graduate employability of planners through unpaid work. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(2), 161-177.

Guomei, T., & Wei, R. (2017). Review on the Impact of Gap Years on Career Development.

Hartl, M. (2009). Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and skills development for poverty reduction–do rural women benefit. Retrieved October, 4, 2011.

Hershatter, A., & Epstein, M. (2010). Millennials and the world of work: An organization and management perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology.

Hodkinson, P., Hodkinson, H., & Sparkes, A. C. (2013). Triumphs and Tears: Young People, Markets, and the Transition from School to Work: Routledge.

Höglund, L., Holmgren Caicedo, M., & Mårtensson, M. (2018). A balance of strategic management and entrepreneurship practices—The renewal journey of the Swedish Public Employment Service. Financial Accountability & Management.

Jackson, D. (2015). Employability skill development in work-integrated learning: Barriers and best practice. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 350-367.

Jung, P., & Kuhn, M. (2014). Labour market institutions and worker flows: comparing Germany and the US. The Economic Journal, 124(581), 1317-1342.

Koen, J., Klehe, U.-C., & Van Vianen, A. E. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 395-408.

Launov, A., & Wälde, K. (2016). The employment effect of reforming a public employment agency. European Economic Review, 84, 140-164.

Lindsay, C., McQuaid, R. W., & Dutton, M. (2008). Inter‐agency cooperation and new approaches to employability. Social Policy & Administration, 42(7), 715-732.

Mamaqi, X. (2015). The efficiency of different ways of informal learning on firm performance: A comparison between, classroom, web 2 and workplace training. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 812-820.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2007). The school-to-work transition: A role identity perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(1), 114-134.

Pastore, F. (2018). Why so slow? The school-to-work transition in Italy. Studies in Higher Education, 1-14.

Quintini, G., Martin, J. P., & Martin, S. (2007). The changing nature of the school-to-work transition process in OECD countries.

Ravenhall, M. (2018). Recognition, validation and accreditation of youth and adult basic education as a foundation of lifelong learning. In. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

Rehwald, K., Rosholm, M., & Svarer, M. (2017). Do public or private providers of employment services matter for employment? Evidence from a randomized experiment. Labour Economics, 45, 169-187.

Riesen, T., Schultz, J., Morgan, R., & Kupferman, S. (2014). School-to-work barriers as identified by special educators, vocational rehabilitation counselors, and community rehabilitation professionals. Journal of Rehabilitation, 80(1), 33.

Ryan, P. (2001). The school-to-work transition: a cross-national perspective. Journal of economic literature, 39(1), 34-92.

Sachrajda, A., & Burnell, E. (2017). Making inclusion work.

Schmid, G. (2015). Sharing risks of labour market transitions: Towards a system of employment insurance. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 53(1), 70-93.

Sultana, R. G., & Watts, A. G. (2006). Career guidance in public employment services across Europe. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6(1), 29-46.

Thorsen, D. (2011). Non-formal apprenticeships for rural youth–questions that need to be asked. NORRAG NEWS, Towards a New Global World of Skills Development? TVET’s turn to Make its Mark(46), 71-73.

Thuy, P., Hansen, E., Price, D., & Perret-Nguyên, H. (2001). The public employment service in a changing labour market: International Labour Office Geneva.

Training, E. C. f. t. D. o. V. (2018). Apprenticeship schemes in European countries: a cross-nation overview. In. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Van Ours, J. C. (1994). Matching unemployed and vacancies at the public employment office. Empirical Economics, 19(1), 37-54.

Wehman, P. (2013). Transition from school to work: where are we and where do we need to go? Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 36(1), 58-66.

Willis, P. (2017). Learning to labour: How working class kids get working class jobs: Routledge.

[1] It’s the mid-point between market flexibility and employment security approach to labour market integration program

[2] De-unionisation, minimum legal wages, unemployment benefits,

[3] Some of them includes (EYG, Good School reform, upscaling pathways, business-education partnership, second chance schools (E2C or ÉCOLES DE LA DEUXIÈME CHANCE), formative island, prospect for young refugees, Fit for the Job for Refugees and London Talent Match and so on

[4] WBL represents the collectivity of range of practical approaches and initiatives to enhance three valuable employability assets of a person; qualification, experience and references through a personalized and intensive process of accessing, mentoring and securing job for unemployed, with especial consideration of disadvantaged population groups. Highly focused skills are communication, languages, critical thinking, problem solving, team work and positive traits, respect for deadlines, adaptability, confidence and motivation, and continues monitoring and evaluation of the initiatives even during post-job placement

[5] There is a provision of voucher (of certain credit amount) for students and can buy education/training hours from any public/private training provider as per the needs and choice of the students

[6] This may include but limited to save money, understand and persevere in relationships, plan and manage a career, recognise and carry out obligations as a citizen, cope with stress, change and insecurity and so on.

[7] In a highly cited theoretical essay (ethnographic research in 1978 in the industrial town of Hammertown of London city), there is a discussion over the pattern of school to work transition among non-academic young school students in relation to the historical characteristics and cultural perception towards manual work carried by their generation and the place they live. YES, still an issue in Western disadvantages areas 40 years on

[8] Characterised by a marked discrepancies emergence in terms of facilities and teacher quality in relation to pedagogic competence, theoretical skills and workplace knowledge, often manifested in outdated curricular.

[9] See more on https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_453913/lang–en/index.htm

[10] See more on https://www.ilo.org/kathmandu/whatwedo/projects/WCMS_377004/lang–en/index.htm

[11] See more on http://www.dol.gov.np/ckeditor/kcfinder/upload/files/ToR-External%20Collaborator%20Employment%20Counsellor%20final.pdf

[12]Web 2.0’’ or ‘‘social computing’’ refers to the range of digital applications that enable interaction, collaboration and sharing between users. See more on page 813, (Mamaqi, 2015).

[13] Gap years means that individuals leave formal learning, training or work places to have a pause or a rest during a period of 3-24 months

[14]Aileen Adalid, one of the traveller from Philippines write in 2015 that Singaporeans and South Koreans can go visa-free to over 163 countries whereas my Philippines passport can only go to 60 countries. There are other passports who have it worse than I do, but certainly, I can’t just go to American or European countries at just about any time without going through rigorous and costly visa applications and strict immigration officers.

Public Employment Agencies

Executive Summary

This is a brief literature review on the public employment agencies (PEAs) across the countries with the objective to identifying major aspect of PEAs explored in the research and see if there are potential areas for future research in the academia.

Key Search Words/phrases: Public Employment Agency, Employment Service Centre, Effectiveness, Efficiency.

Introducing Public Employment Agency

Public Employment Agency (PEA) is a government entity, usually responsible for assisting citizens for job search, vocational guidance and distribution of unemployment benefits (Fougere, Pradel, & Roger, 2009). Nevertheless, its functions may be one or more of the above functional items across the countries depending upon the nature of the labour market and development status of the countries(Thuy, Hansen, Price, & Perret-Nguyên, 2001). There are private employment agencies too, which do similar functions often more ‘intense and costly services’ but target different type of job seekers, usually who can afford job search cost (Fay, 1997; Rehwald, Rosholm, & Svarer, 2017).

Different terms represent the public employment agencies across the world; ‘job brokerage agencies’ in Europe (Launov & Wälde, 2016), Public Employment Service in various member states of ILO(Thuy et al., 2001), employment service office in Australia (Fay, 1997), public employment service in Sweden (Höglund, Holmgren Caicedo, & Mårtensson, 2018), job centre in South Korea[1] and Jobcentre plus in UK(Lindsay, McQuaid, & Dutton, 2008, p. 722), Employment Service Centre (ESC) in Nepal[2] , temporary work agency and so on.

Personnel working in the PEAs are also recognized by different names including job broker in Europe(Commission, 2016), employment counsellor in Nepal[3], job agents, placement officers, employment out-reach personnel and employment specialist in Taiwan, employment advisor in France (Sultana & Watts, 2006), employment coaches in UK (Lindsay et al., 2008, p. 726)and case managers in Australia (Fay, 1997) and so on.

PEAs’s clients are job seekers, training organizations and employment {Commission, 2016, p.25}.

History of Public Employment Agency

Public Employment Service (PES) have history of its existence around the end of the 19th century mainly to tackle the socio-economic challenges posed by the unemployment however it was ILO (established in 1919) which formally established PES in different developing countries. During World War II, PES were involved in job broking or labour exchange and distribution of unemployment benefit however after 1970s, owning to high growth of unemployment, PES became government entity in developing countries for developing employment policies and labour market programs. Around 1990s, owing to the growing impact of economic liberalisation and globalization, there were the emergence of private employment agencies (Thuy et al., 2001).

Functions and Role of PEAs

Basically, PEAs are observed to be doing 2 major functions; first job search assistance and vocational guidance in developing countries particularly focusing on unemployed youth, and secondly distribution of unemployment benefit to short-term and long-term job seekers based on ‘work-test function’[4] as well as management of ageing labour force in developed countries (Rehwald et al., 2017; Sultana & Watts, 2006; Thuy et al., 2001).

Various studies focus on the standard functional aspect of the PEAs across the countries. They include 1) personalisation of services, which support client on an individual basis for job search, counselling and other services 2) assessment of individual attribute and preferences 3) short-term job placement and long-term career strategies 4) develop a personalised action plan(Sultana & Watts, 2006). Some also advocate for policy-making role of PEAs apart from work-test functions and job search assistance role (Thuy et al., 2001).

Various Aspects of Public Employment Agency

Various facets of PEA are explored in the research studies; the ways of enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of PEAs through various job-search and job-matching models (Fay, 1997; Fougere et al., 2009; Van Ours, 1994), need of labour market reform activity including unemployment compensation system, VET provision, trade unions, labour taxation, subsidies and employment protection (Sultana & Watts, 2006; Thuy et al., 2001). Some made the inquiry into what kind of relationship should be there between PEA and other organization including government and non-governmental organisation, private agencies and community organizations? (Thuy et al., 2001). Few also raised the question; How the efficiency and equity objectives of PEAs considering disadvantaged population can be achieved? (Fay, 1997; Fougere et al., 2009; Thuy et al., 2001)

Research Gaps

Majority of research contexts are limited within the formal labour market where there is the availability of statistical data on labour market information (like exit from unemployment), especially that of European and United states countries where there is the provision of unemployment benefits and active labour market programs like provision of vocational training in their domestic market. However, the rural contexts of public employment agency struggling in highly informal and poor economy with distinctive geographical and socio-economic barriers for accessing job seekers and employers (education, skills, awareness, public services, social marginality and so on) have got relatively less attention.

While studying the effectiveness and efficiency of the PEAs, the major studies take statistical approaches (IPA technique, partial equilibrium unemployment, reduced form model of job search, structural model of job search and their disincentive effects etc) to analyse the functional aspect of PEAS like job search, job placement, and its effect on the exit from unemployment, often looked as the indicators of operational effectiveness of PEAs. This suggests a lack of qualitative research approach to study the effectiveness of PEAs in terms of the attainment of equity objectives like inclusion of disadvantaged youth in the labour market. Some even consider for the assessment of the role of mutual partnership among employment agencies (both public and private), VET institutions, government and non-governmental organizations and community partners in strengthening the position of PEAs. (Thuy et al., 2001; Van Ours, 1994).

References

Commission, E. (2016). job broker project – competency and learning development for job brokers in the EU Intellectual Output 02

In (pp. 40). Europe: Job Broker.

Fay, R. G. (1997). Making the public employment service more effective through the introduction of market signals.

Fougere, D., Pradel, J., & Roger, M. (2009). Does the public employment service affect search effort and outcomes? European Economic Review, 53(7), 846-869.

Höglund, L., Holmgren Caicedo, M., & Mårtensson, M. (2018). A balance of strategic management and entrepreneurship practices—The renewal journey of the Swedish Public Employment Service. Financial Accountability & Management.

Launov, A., & Wälde, K. (2016). The employment effect of reforming a public employment agency. European Economic Review, 84, 140-164.

Lindsay, C., McQuaid, R. W., & Dutton, M. (2008). Inter‐agency cooperation and new approaches to employability. Social Policy & Administration, 42(7), 715-732.

Rehwald, K., Rosholm, M., & Svarer, M. (2017). Do public or private providers of employment services matter for employment? Evidence from a randomized experiment. Labour Economics, 45, 169-187.

Sultana, R. G., & Watts, A. G. (2006). Career guidance in public employment services across Europe. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6(1), 29-46.

Thuy, P., Hansen, E., Price, D., & Perret-Nguyên, H. (2001). The public employment service in a changing labour market: International Labour Office Geneva.

Van Ours, J. C. (1994). Matching unemployed and vacancies at the public employment office. Empirical Economics, 19(1), 37-54.

[1] See more on https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_453913/lang–en/index.htm

[2] See more on https://www.ilo.org/kathmandu/whatwedo/projects/WCMS_377004/lang–en/index.htm

[3] See more on http://www.dol.gov.np/ckeditor/kcfinder/upload/files/ToR-External%20Collaborator%20Employment%20Counsellor%20final.pdf

[4] PEA officials determine if the clients is eligible to receive the unemployment benefits through testing his work history and job search activity and results

Understanding Institutional Field Theory

Key Words: Institutional Theory, Institutional Field Theory, Organizational Field Theory

In simple term, the general theory of organization seems to put organizations or institutions (interchangeably used) as the central component of the society as its significant construct and study how social behaviours and action occur.

There are various theoretical discussions and suggestions for consideration over the field theory since the 19th century. Max Weber studied bureaucratization as the main organizational form and change and analyzed the various causal factors, among whom ‘the competition among capitalist firms’ stood as the most important. However, there is a claim that the causal factor of bureaucratization also implied in ‘engine of rationalization’ has changed, maintaining the claim that the organizational form is same (highly bureaucratized like iron cage). Theorists claim that after a more than 8 decades of Max Weber’s theory on the Institutional field, the three causal aspects ‘mimetic, coercive and normative’ also termed as ‘isomorphic processes’ remains that major characteristic of the organizational field in the contemporary context (end of 20th century). According to the DiMaggio and Powell, the state and the professions should be attributed for change ‘organizational ‘homogeneity’ rather than diversity’ in the organizational field, in compare to the Max Weber’s ‘competition among the capitalist firms’. Those isomorphic change process were resulted by the powerful forces of state and professionals, leading existing organizations and new entrants to the competitive market follow the same organizational rationalization process (DiMaggio and Powell 1983).

Research by Mazza and Pedersen (2004) shows how the state pressures (European Union consolidation) and financial shocks (oil crisis, economic downturn) were among change factors responsible for transformation ‘patterned behavioural change’ among media publishing organisations in two European countries namely Italy and Denmark.

Some searchers Woodward, Child and Kieser were interested in knowing ‘why there are so many organizations?’, ‘why are they so different types of organization?’ while DiMaggio and Powell were interested to know ‘why are organizations showing so much similarity in structure, culture and out?’

DiMaggio and Powell refers to the cases of different organisational studies (hospital, public schools, legal education system, radio industry, high culture in late 19th Century, civil service reform in US, ) and inquire why all of these, despite having different activities and definitions, ultimately end of having dominant forms, structures or organization models or ‘homogeneity’? (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), and hence highlighting the connectedness and structural equivalence as the major form of interactions among the organization to give rise to a recognized area of institutional life. Organizational field exist only through the experience of their initial life or empirical investigation (not due to priori definition based on theory) which can be understood in terms of 4 factors namely 1) an increase in the extent of interaction among organizations in the field 2) the emergence of sharply defined inter-organizational structures of domination and patters of coalition 3) an increase in the information load with which organizations in a field must contend; 4) and the development of a mutual awareness among participants in a set of organizations that they are involved in a common enterprise`

DiMaggio and Powell argue which factor affect more? Is it ‘competition’ or ‘state’ or ‘professions’? in isomorphism. A researcher noted (DiMaggio and Powell 1983) as Hawley, attribute isomorphism among organizations through the selection of competitive and strongly existing organizations while weaker one ‘non-optimal’ not selected, which give rise to the similar organizational field. According to them, ‘The theory of isomorphism addresses not the psychological states of actors but the structural determinants of the range of choices that actors perceive as rational or prudent’. The concept of institutional isomorphism is a useful tool for understanding the politics and ceremony that pervade much modern organizational life. They imply that public service policy maker should consider organizational form, their trend of diversification and homogenization, rather than a program of individual organizations while formulating policy favouring the pluralism.

Some (Davis and Marquis 2005), referring to the context of 21st century discusses organizational field theory or ‘‘phrenology of social sciences’’ as a tool to study the natural history of the organizational in the context of the contemporary capitalism (globalization, the emphasis over service-based industry in compare to manufacturing industries). Davis and Marquis (2005) argue that the type of interactions between organizations or organizational fields (which has changed in 21st century context) can provide better framework to study social change more appropriately, not just being limited to the study of the trend of “death and birth rate of companies” of any particular field studies in 20th century.